|

|

#1

|

|||

|

|||

|

Just stumbled across this after all of this time. Been muddling through for about 40 years. Realising that there is so much more to this game than scales and how to stack the harmony notes onto scale degrees.

Came across the cycle of fifths years ago. Didn't really understand it then. Not like I think I do now! ;o) Playing stuff now that has a new dimension to it. Wow, feel so grateful. I can see now how the Beatles chose some of the chords they did. |

|

#2

|

||||

|

||||

|

I dont understand any of that, but I like it when I hear it! Sometimes I accidently stumble across a bizarre, but beautiful chord. I diagram it, but usually fail to find what or how it happened!

|

|

#3

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

So what I was trying to say was I’d discovered how to use secondary dominant seventh chords. For example, rather than just change from Cmaj to Amin, use E7 to link the two. So the profession becomes C E7 Amin. So, by taking the 5th note of the destination chord (E in this case, the fifth note from A min (ACE)) and use that note to establish the secondary dominant to link the chords together. I’ve tried this method to identify great chords to spice up progressions. I also meant ask if others were using this kind of thing? I hope that makes it clearer? |

|

#4

|

|||

|

|||

|

I started with songwriting decades ago, and the chords I chose were strictly by whim and ear. "Let me try this, hmm, how about this? Hey, that sounds interesting/good." Then later I sort of learned the chords associated simply with the major and minor scales, and understood them to be the "correct" ones. Songwriting life was made simple.

Eventually I moved on to instrumental music and a major way my expression there worked was to consider all notes as plausible against any chord,* and that this worked best if the harmonic structure was kept simple. So while my melodic work implied harmonic movement, I was not long concerned with harmonic progressions as such. Now in the past four years I've started to call myself a "composer" which sounds too high-falutin for what I do, but is more honest than calling myself a musician which I think implies that I have a certain range of playing concepts under my hands, when I don't. That lead me to start to reexamine the frameworks of functional harmony: why we might choose certain chords in certain order and what happens when we confound expectations or common tendencies. I'm a rank beginner, so I might help others for whom this sounds esoteric: You can pleasantly use a chord or more that aren't in the seven chords that are harmonized off the major or minor scale,** the "right chords" that get used all the time. They make sense to be considered as if one has momentarily modulated (like the old songwriters trick of using a different key for the chorus or bridge, only more briefly). As in the example above this doesn't need to sound "out" or anything, it can just be a different pleasant sound. You can even use a very wrong chord between two "right" chords in passing and add flavor (much like the old improvisor's maxim that if you play a "out" or "wrong" note by accident, if you can resolve it it'll "sound like jazz.") One way to make sense out this, to say why it works when it sounds pleasant is rationalize how it relates the the "right chords" in another key related to the piece's "home" key--and a common gateway, the little musical wormhole, is to make the leap is around the "strong" chords in the home key, like the dominant (in the key of C, G). *This doesn't mean musical nihilism, only that one can expand one's choices considerably beyond the "right notes" and still make sense in a pattern or pleasurable sounds to some ears/minds. **so in C Major the "right chords" are C Dm Em F G Am Bdim, and a whole lot of songs never use a chord that isn't in that series.

__________________

----------------------------------- Creator of The Parlando Project Guitars: 20th Century Seagull S6-12, S6 Folk, Seagull M6; '00 Guild JF30-12, '01 Martin 00-15, '16 Martin 000-17, '07 Parkwood PW510, Epiphone Biscuit resonator, Merlin Dulcimer, and various electric guitars, basses.... |

|

#5

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Some of the first songs I ever learned on guitar (early blues and jazz) had secondary dominants. Of course I didn't know that's what they were called - any more than the Beatles did! Everyone then just learned what they liked from existing songs. You didn't have to care (or even know) about theory, or question anything you found. Obviously it sounded good, so you played it. I'm sure, in those 40 years you've been playing, you must have played lots of secondary dominants without being aware of it. It's hard to imagine how you might have avoided them entirely. It's true you don't get many in folk songs, but you get them in country and plenty of pop songs, sometimes in blues - not just in jazz.

__________________

"There is a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in." - Leonard Cohen. |

|

#6

|

|||

|

|||

|

For others interested/baffled, here's the theory:

Secondary dominants in C major: D = V/V = dominant of V (leads to G) A = V/ii = dominant of ii (leads to Dm) E = V/vi = dominant of vi (leads to Am) B = V/iii = dominant of iii (leads to Em) C7 = V/IV = dominant of IV (leads to F) Notice only the last one actually needs a 7th. The other four are "dominant" because of their V relationship to the following chord and their chromatic (out of key) major 3rds, which act as "leading tones" up to the next root note. C already has a major 3rd, of course, as the diatonic I chord, so needs a chromatic b7 (Bb) to mark it as V of F and lead down to A on the F chord. Of course, you can add 7ths to the other four if you like, they help increase the tension, but their 7ths are all diatonic to C major. You don't have to know any of this theory, of course. You don't have to know any theory at all! In fact the problem with learning theory is you can start to think it's rules you are supposed to follow - which has two disadvantages: (1) it restricts what you think you can do when writing songs ; (2) it makes you think some songs are "breaking rules", or makes you question what you are hearing.

__________________

"There is a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in." - Leonard Cohen. Last edited by JonPR; 07-10-2020 at 09:49 AM. |

|

#7

|

|||

|

|||

|

As JonPR says, you can't play jazz without tripping over secondary dominants everywhere.

Even before I knew that there was a name for it, I could hear it in a lot of popular music going back to the turn of last century. Turns out that it is a mainstay of classical music going back hundreds of years. I think of secondary dominants as the most accessible form of modulation within a diatonic space. It's relatively easy on the ear and somewhat hard to make sound bad. Good that you are discovering this, it should open many doors for you.

__________________

-Gordon 1978 Larrivee L-26 cutaway 1988 Larrivee L-28 cutaway 2006 Larrivee L03-R 2009 Larrivee LV03-R 2016 Irvin SJ cutaway 2020 Irvin SJ cutaway (build thread) K+K, Dazzo, Schatten/ToneDexter Notable Journey website Facebook page Where the spirit does not work with the hand, there is no art. - Leonardo Da Vinci |

|

#8

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

|

|

#9

|

|||

|

|||

|

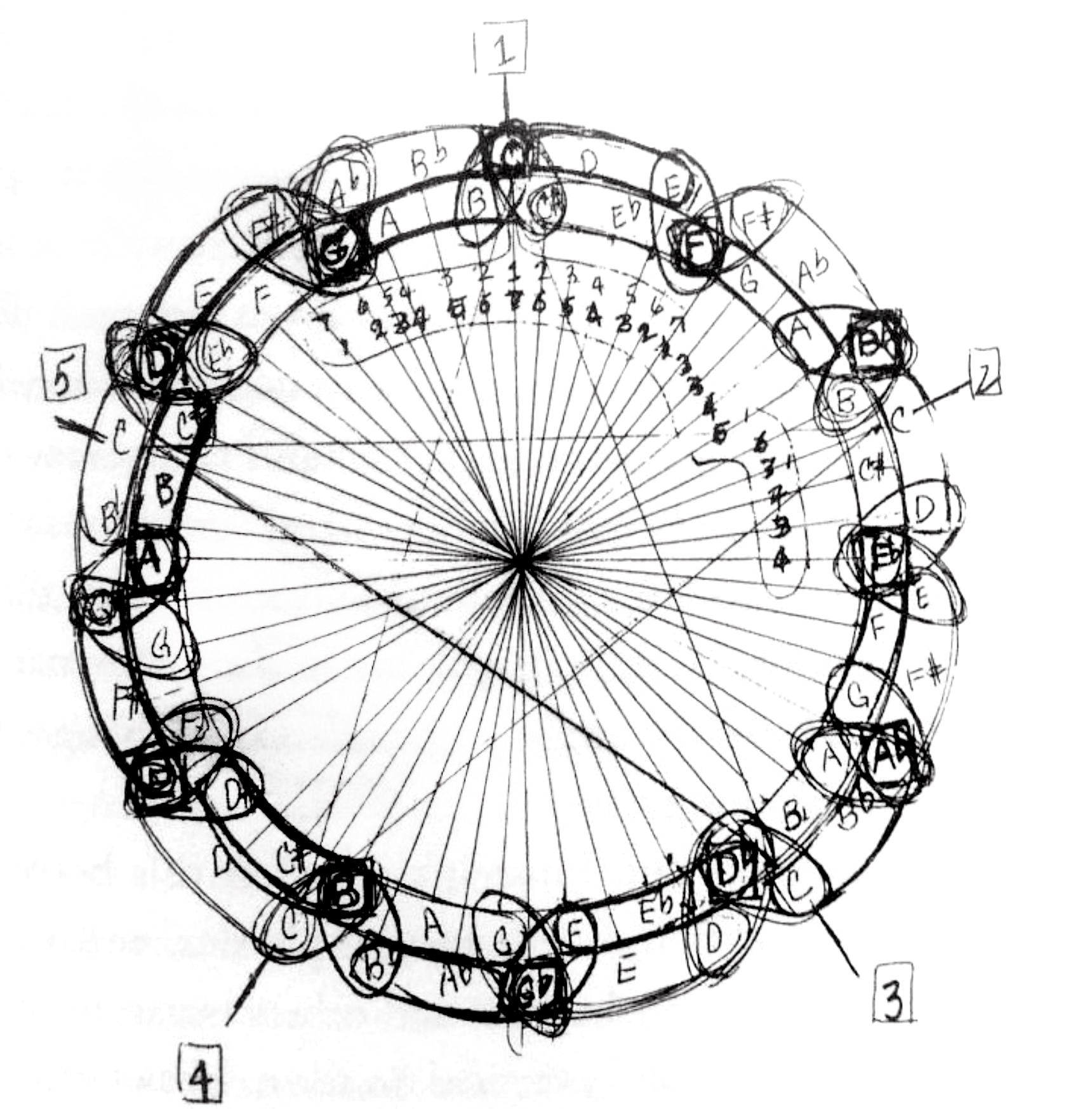

JOHN COLTRANE’S DRAWING OF THE MATHEMATICAL SOUL OF MUSIC

https://www.faena.com/aleph/articles...soul-of-music/

__________________

https://www.youtube.com/user/wags2413/videos |

|

#10

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

Both V/V and V/IV have the fifth and the lead tone of the next chord D : D (=5 of G), F# (=lead tone of G) C : C (=5 of F), E (=lead tone of F) C7 : extra Bb leads indeed down to A (third of F) but the same goes for D7 : extra C which also leads down to B (the third of G) |

|

#11

|

|||

|

|||

|

Because only the leading tone is required for the others to have their "dominant" relationship to the following chord.

In all those, their major 3rds are chromatic, for that purpose: an alteration of the diatonic note to form a leading tone to the next root, and to distinguish them from the usual minor chord in that position (or the dim or m7b5 where the V/iii would normally be). With the tonic chord, its major 3rd is diatonic. It certainly leads up to the IV, but as a triad it's simply the "I" chord - the primary tonic, not a secondary dominant. Adding the chromatic b7 is necessary to define it as V/IV. With the other four secondary dominants, yes the 7ths form additional leading tones downwards, but they are all diatonic. The C on a D7 (in key of C major) is the same as the C on Dm7. Dm7 is the ii chord, not a secondary chord of any kind. It's raising the F to F# that turns it into a "secondary dominant", and the 7th is merely an optional decoration. It works as V/V whether it has a C on it or not. The C major chord can't really work as V/IV unless it has the 7th added.

__________________

"There is a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in." - Leonard Cohen. |

|

#12

|

|||

|

|||

|

I started playing about with this stuff back in the 1960s when I discovered songs like Sweet Georgia Brown. I found I could go from C to C7 to F, then F to F7 to B flat. Then B flat to B flat7 to E flat. E flat, A flat, D flat, G flat. Somewhere round there I started thinking in sharps so G flat became F# and F#7 changed to B, B7 to E, E7 to A, A7 to D, D7 to G and G7 back to C. A great exercise for those who are coming to terms with bar chords. There were twelve steps, each a perfect fourth although back then I didn't know what 'fourth' meant. Funny that I could use the idea without knowing it's name.

I now know that that was the 'chromatic' route. It was chromatic because it made a chord from every one of the twelve available notes rather than sticking to just the seven notes in the major scale. Sticking to just the seven notes of the major scale is the 'diatonic' route. That in itself is an interesting sequence and another good exercise in bar chords. Code:

C F Bdim(G7) Em Am Dm G C The triad built on the note B contains the notes B, D and F. The intervals between B and D and between D and F are both minor thirds so it is neither a major nor a minor chord. It's a diminished chord. Those of you who know the notes in your basic chords might have spotted that the notes B, D and F, added to the note G make up the chord of G7. In this sequence you can replace Bdim with G7 although it's root is still B. Again the intervals between these chords are all fourths but the fourth between F and B is one fret larger than all the other intervals. All the other intervals are five frets, perfect fourths. F to B is six frets. It's an augmented fourth. Jumping that one extra fret gets you back to C in seven steps instead of twelve. |

|

#13

|

|||

|

|||

|

Quote:

|